What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples

Content validity evaluates how well an instrument (like a test) covers all relevant parts of the construct it aims to measure. Here, a construct is a theoretical concept, theme, or idea: in particular, one that cannot usually be measured directly.

Content validity is one of the four types of measurement validity. The other three are:

- Face validity: Does the content of the test appear to be suitable for its aims?

- Criterion validity: Do the results accurately measure the concrete outcome they are designed to measure?

- Construct validity: Does the test measure the concept that it’s intended to measure?

Content validity examples

Some constructs are directly observable or tangible, and thus easier to measure. For example, height is measured in inches. Other constructs are more difficult to measure. Depression, for instance, consists of several dimensions and cannot be measured directly.

When developing a depression scale, researchers must establish whether the scale covers the full range of dimensions related to the construct of depression, or only parts of it. If, for instance, a proposed depression scale only covers the behavioral aspects of depression and neglects to include affective ones, it lacks content validity and is at risk for research bias.

Additionally, in order to achieve content validity, there has to be a degree of general agreement, for example among experts, about what a particular construct represents.

Research has shown that there are at least three different components that make up intelligence: short-term memory, reasoning, and a verbal component.

This means that existing IQ tests do not sufficiently cover all the dimensions of what constitutes human intelligence. To do so, three separate tests would be needed to test each dimension. Thus, these tests are considered to have low content validity.

Construct vs. content validity example

It can be easy to confuse construct validity and content validity, but they are fundamentally different concepts.

Construct validity evaluates how well a test measures what it is intended to measure. If any parts of the construct are missing, or irrelevant parts are included, construct validity will be compromised. Remember that in order to establish construct validity, you must demonstrate both convergent and divergent (or discriminant) validity.

- Convergent validity shows whether a test that is designed to measure a particular construct correlates with other tests that assess the same construct.

- Divergent (or discriminant) validity shows you whether two tests that should not be highly related to each other are indeed unrelated. There should be little to no relationship between the scores of two tests measuring two different constructs.

On the other hand, content validity applies to any context where you create a test or questionnaire for a particular construct and want to ensure that the questions actually measure what you intend them to.

- High content validity: If your survey questions cover all dimensions of health needs, i.e., physical, mental, social, and environmental, your questionnaire will have high content validity.

- Low content validity: If some dimensions of health needs are omitted, the results may not provide an accurate indication of community health needs.

- High convergent validity: If the answers to your survey questions correlate with the answers to existing health needs surveys , then this is an indication that your measure probably has high construct validity. However, make sure to keep in mind that in order to demonstrate construct validity, you must demonstrate both convergent and divergent (or discriminant) validity.

- Low discriminant validity: If most of your survey questions correlate strongly with existing measures of the population’s attitudes toward health services , then the results are likely no longer a valid measure of the health needs of the community. In other words, your survey seems to measure a different construct (attitude) than intended (health needs). Therefore, it has low construct validity.

In both cases, the questionnaire would have low content validity.

Step-by-step guide: How to measure content validity

Measuring content validity correctly is important—a high content validity score shows that the construct was measured accurately. You can measure content validity following the step-by-step guide below:

- Step 1: Collect data from experts

- Step 2: Calculate the content validity ratio

- Step 3: Calculate the content validity index

Step 1: Collect data from experts

Measuring content validity requires input from a judging panel of subject matter experts (SMEs). Here, SMEs are people who are in the best position to evaluate the content of a test.

For example, the expert panel for a school math test would consist of qualified math teachers who teach that subject.

For each individual question, the panel must assess whether the component measured by the question is “essential,” “useful, but not essential,” or “not necessary” for measuring the construct.

The higher the agreement among panelists that a particular item is essential, the higher that item’s level of content validity is.

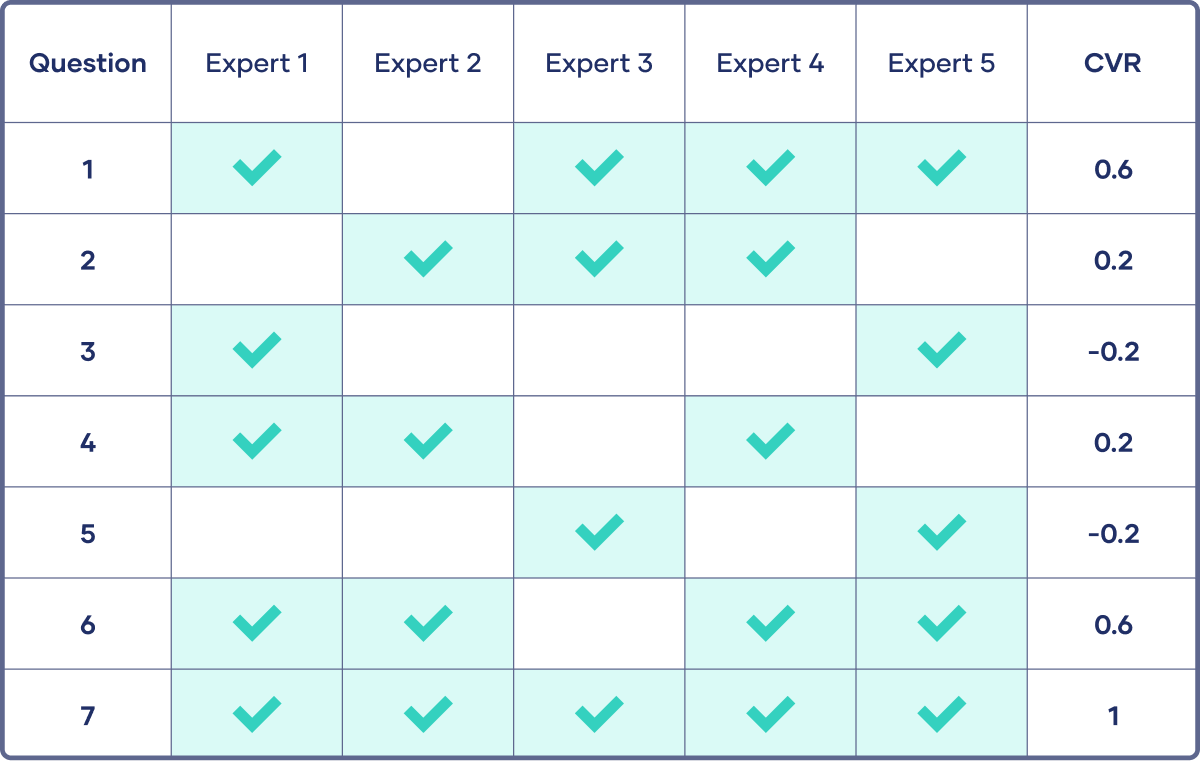

Step 2: Calculate the content validity ratio

Next, you can use the following formula to calculate the content validity ratio (CVR) for each question:

Content Validity Ratio = (ne − N/2) / (N/2)

where:

- ne = number of SME panelists indicating “essential”

- N = total number of SME panelists

The content validity ratio for the first question would be calculated as:

Content Validity Ratio = (ne − N/2) / (N/2) = (4 − 5/2) / (5/2) = 0.6

Using the same formula, you calculate the CVR for each question.

Note that this formula yields values which range from +1 to −1. Values above 0 indicate that at least half the SMEs agree that the question is essential. The closer to +1, the higher the content validity.

However, agreement could be due to coincidence. In order to rule that out, you can use the critical values table below. Depending on the number of experts in the panel, the content validity ratio (CVR) for a given question should not fall below a minimum value, also called the critical value.

| # of panelists | Critical value |

|---|---|

| 5 | 0.99 |

| 6 | 0.99 |

| 7 | 0.99 |

| 8 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 0.78 |

| 10 | 0.62 |

| 11 | 0.59 |

| 12 | 0.56 |

| 20 | 0.42 |

| 30 | 0.33 |

| 40 | 0.29 |

Step 3: Calculate the content validity index

To measure the content validity of the entire test, you need to calculate the content validity index (CVI). The CVI is the average CVR score of all questions in the test. Remember that values closer to 1 denote higher content validity.

To calculate the content validity index (CVI) of the entire test, you take the average of all the CVR scores of the seven questions.

Here, that would be:

Comparing the CVI with the critical value for a panel of 5 experts (0.99), you notice that the CVI is too low. This means that the test does not accurately measure what you intended it to. You decide to improve the questions with a low CVR, in order to get a higher CVI.

Other interesting articles

If you want to know more about statistics, methodology, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

Frequently asked questions about content validity

- In what ways are content and face validity similar?

-

Face validity and content validity are similar in that they both evaluate how suitable the content of a test is. The difference is that face validity is subjective, and assesses content at surface level.

When a test has strong face validity, anyone would agree that the test’s questions appear to measure what they are intended to measure.

For example, looking at a 4th grade math test consisting of problems in which students have to add and multiply, most people would agree that it has strong face validity (i.e., it looks like a math test).

On the other hand, content validity evaluates how well a test represents all the aspects of a topic. Assessing content validity is more systematic and relies on expert evaluation. of each question, analyzing whether each one covers the aspects that the test was designed to cover.

A 4th grade math test would have high content validity if it covered all the skills taught in that grade. Experts(in this case, math teachers), would have to evaluate the content validity by comparing the test to the learning objectives.

- What’s the difference between content and construct validity?

-

Construct validity refers to how well a test measures the concept (or construct) it was designed to measure. Assessing construct validity is especially important when you’re researching concepts that can’t be quantified and/or are intangible, like introversion. To ensure construct validity your test should be based on known indicators of introversion (operationalization).

On the other hand, content validity assesses how well the test represents all aspects of the construct. If some aspects are missing or irrelevant parts are included, the test has low content validity.

- Why is content validity important?

-

Content validity shows you how accurately a test or other measurement method taps into the various aspects of the specific construct you are researching.

In other words, it helps you answer the question: “does the test measure all aspects of the construct I want to measure?” If it does, then the test has high content validity.

The higher the content validity, the more accurate the measurement of the construct.

If the test fails to include parts of the construct, or irrelevant parts are included, the validity of the instrument is threatened, which brings your results into question.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. (2023, June 22). What Is Content Validity? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved January 8, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/content-validity/